neocaml 0.1 is finally out! Almost a year

after I announced the

project,

I’m happy to report that it has matured to the point where I feel comfortable

calling it ready for action. Even better - neocaml recently landed in

MELPA, which means installing it is now as easy

as:

1

| M-x package-install <RET> neocaml <RET>

|

That’s quite the journey from “a fun experimental project” to a proper Emacs

package!

Why neocaml?

You might be wondering what’s wrong with the existing options. The short answer -

nothing is wrong per se, but neocaml offers a different set of trade-offs:

caml-mode is ancient and barely maintained. It lacks many features that

modern Emacs users expect and it probably should have been deprecated a long time ago.tuareg-mode is very powerful, but also very complex. It carries a lot of

legacy code and its regex-based font-locking and custom indentation engine show

their age. It’s a beast - in both the good and the bad sense of the word.neocaml aims to be a modern, lean alternative that fully embraces

TreeSitter. The codebase is small, well-documented, and easy to hack on. If

you’re running Emacs 29+ (and especially Emacs 30), TreeSitter is the future

and neocaml is built entirely around it.

Of course, neocaml is the youngest of the bunch and it doesn’t yet match

Tuareg’s feature completeness. But for many OCaml workflows it’s already more

than sufficient, especially when combined with LSP support.

I’ve started the project mostly because I thought that the existing

Emacs tooling for OCaml was somewhat behind the times - e.g. both

caml-mode and tuareg-mode have features that are no longer needed

in the era of ocamllsp.

Let me now walk you through the highlights of version 0.1.

Features

The current feature-set is relatively modest, but all the essential functionality

one would expect from an Emacs major mode is there.

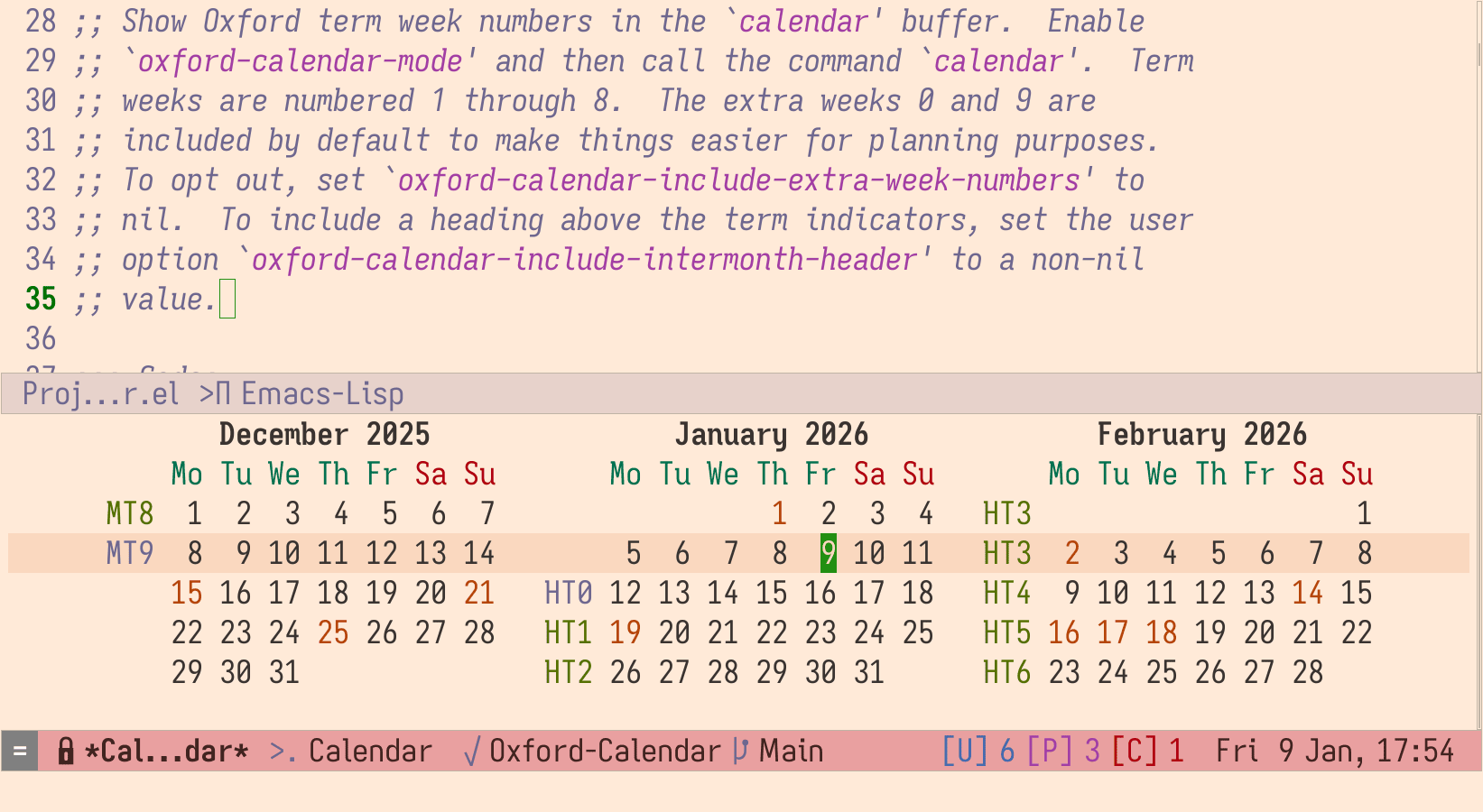

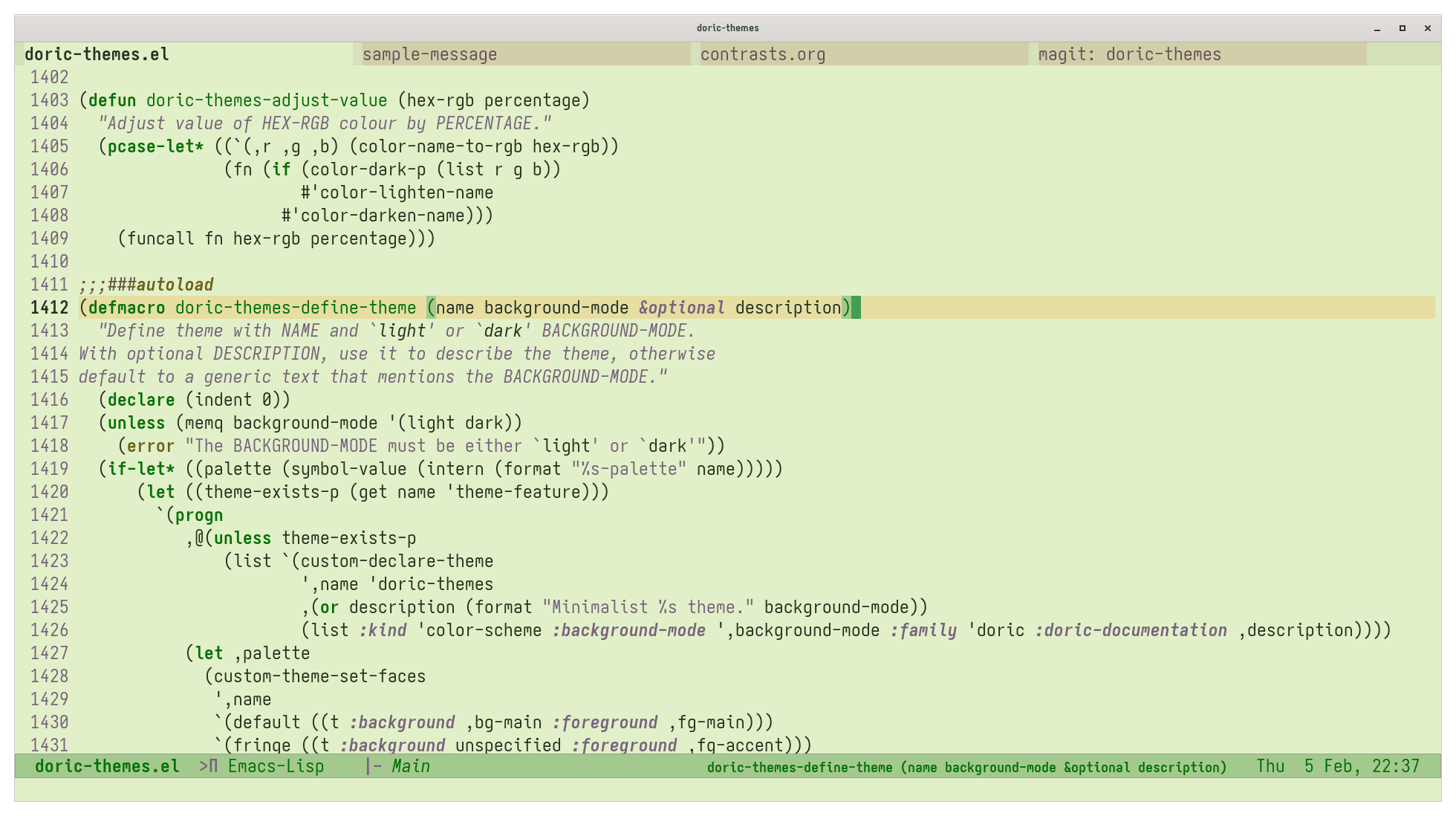

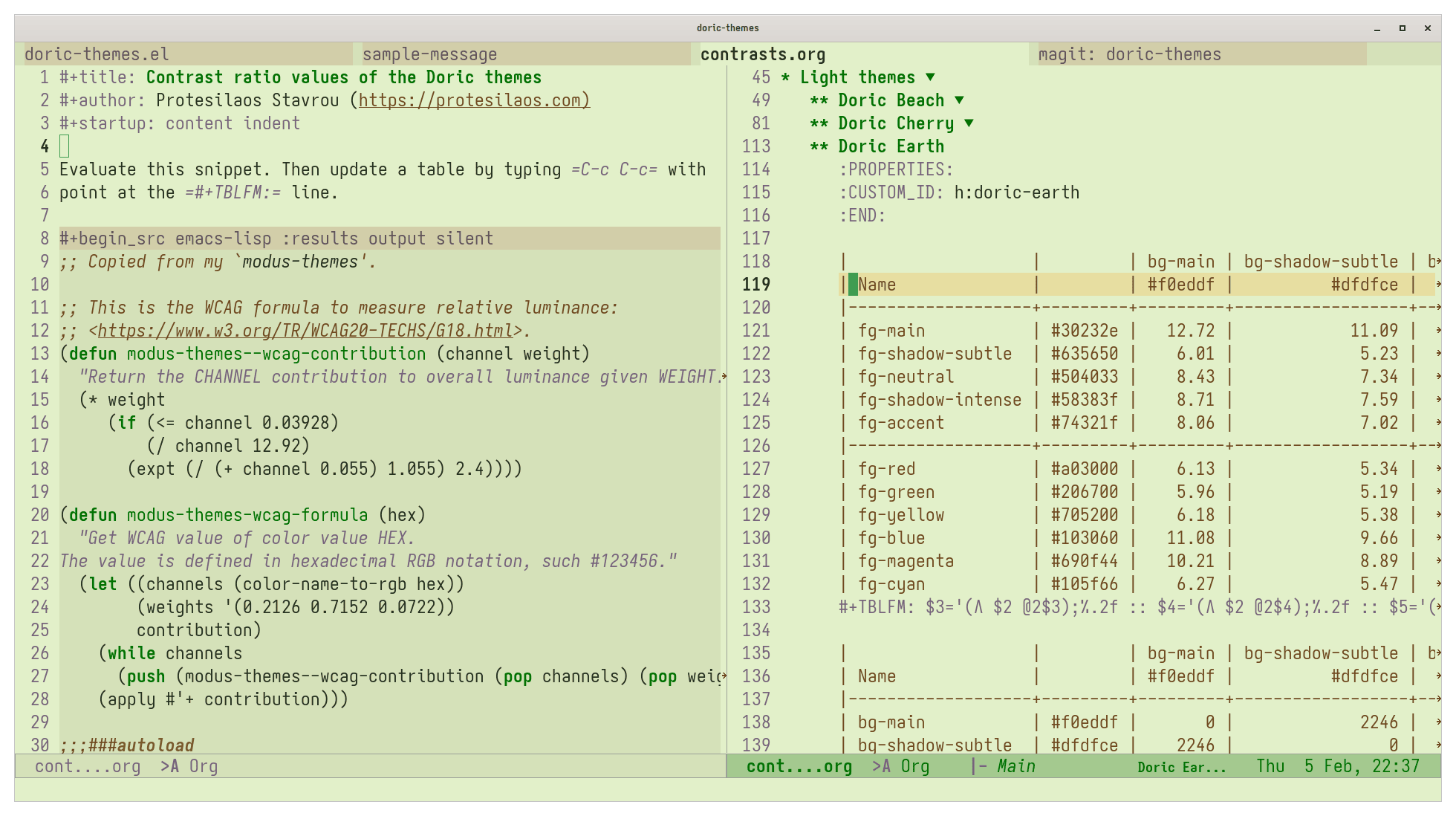

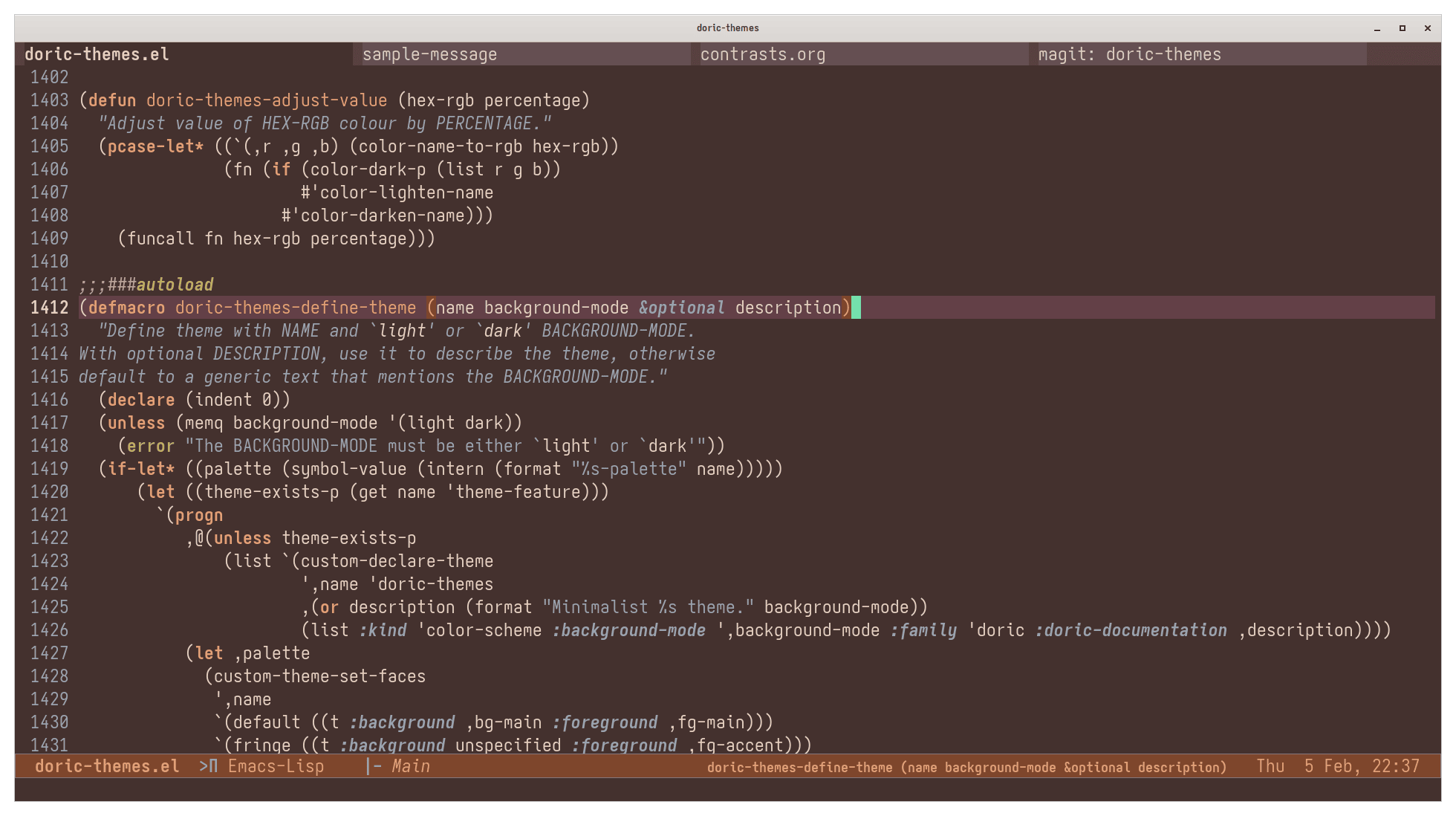

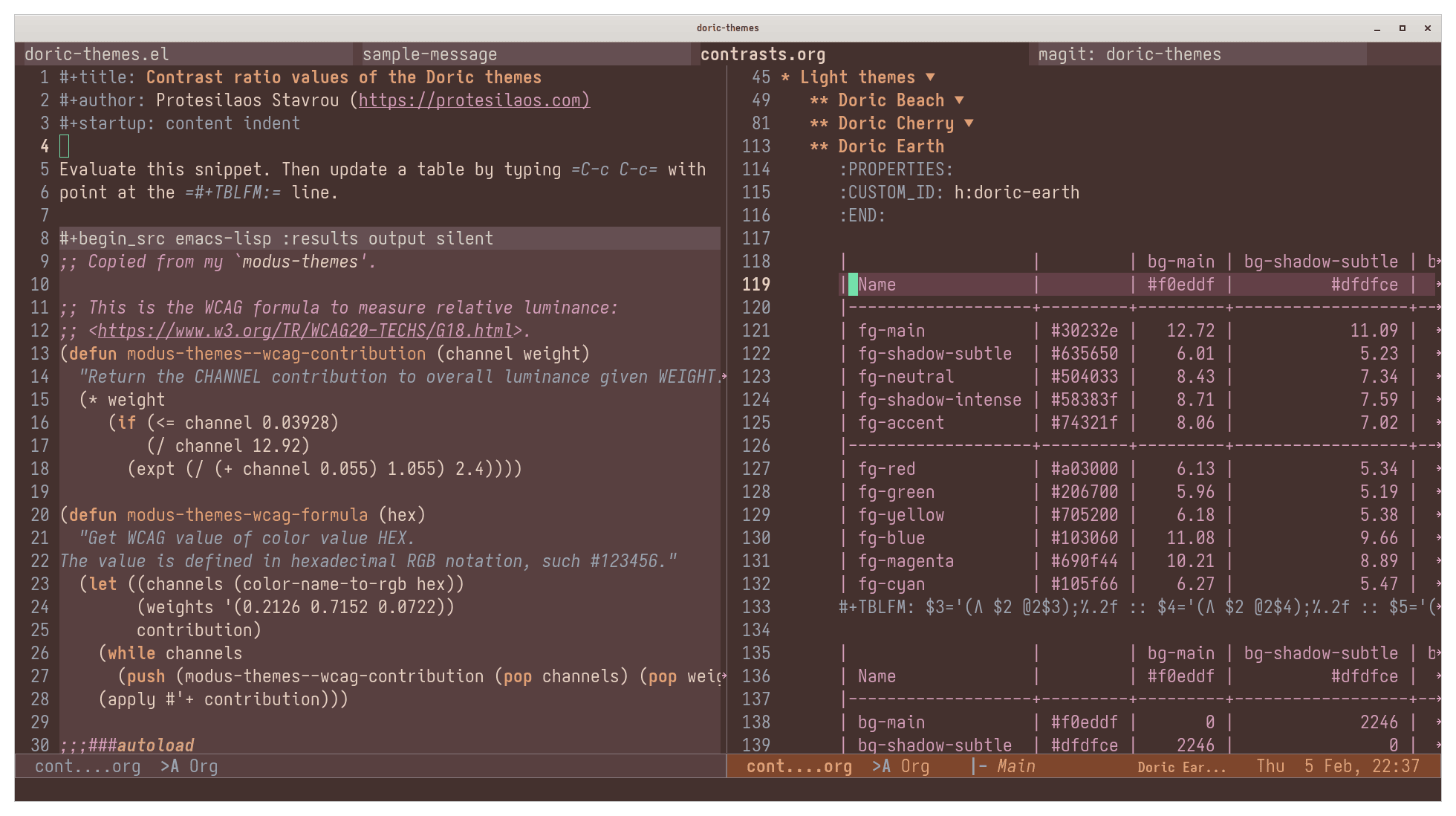

TreeSitter-powered Syntax Highlighting

neocaml leverages TreeSitter for syntax highlighting, which is both more

accurate and more performant than the traditional regex-based approaches used by

caml-mode and tuareg-mode. The font-locking supports 4 customizable

intensity levels (controlled via treesit-font-lock-level, default 3), so you

can pick the amount of color that suits your taste.

Both .ml (source) and .mli (interface) files get their own major modes with

dedicated highlighting rules.

TreeSitter-powered Indentation

Indentation has always been tricky for OCaml modes, and I won’t pretend it’s

perfect yet, but neocaml’s TreeSitter-based indentation engine is already quite

usable. It also supports cycle-indent functionality, so hitting TAB repeatedly

will cycle through plausible indentation levels - a nice quality-of-life feature

when the indentation rules can’t fully determine the “right” indent.

If you prefer, you can still delegate indentation to external tools like

ocp-indent or even Tuareg’s indentation functions. Still, I think most people

will be quite satisfied with the built-in indentation logic.

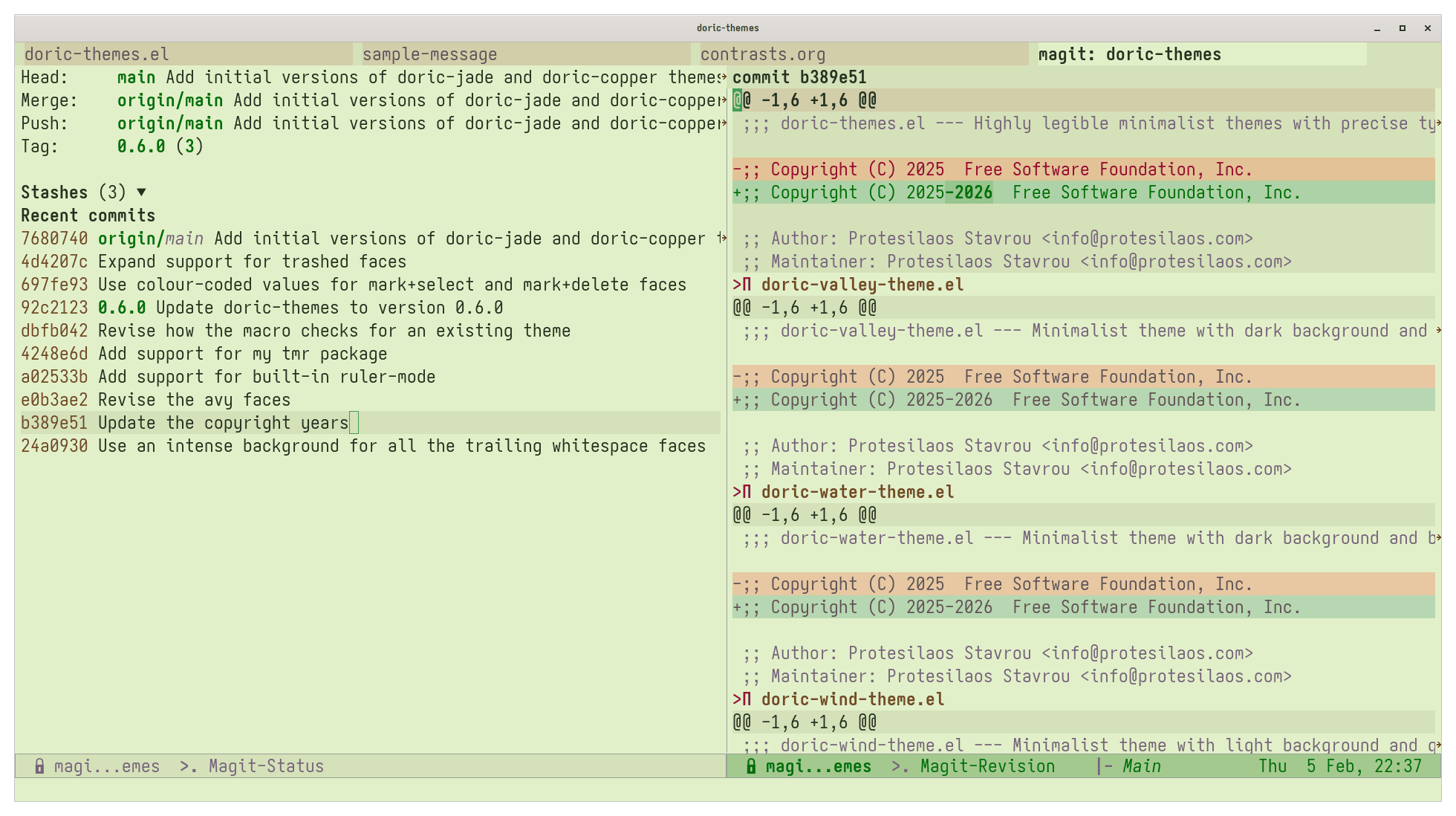

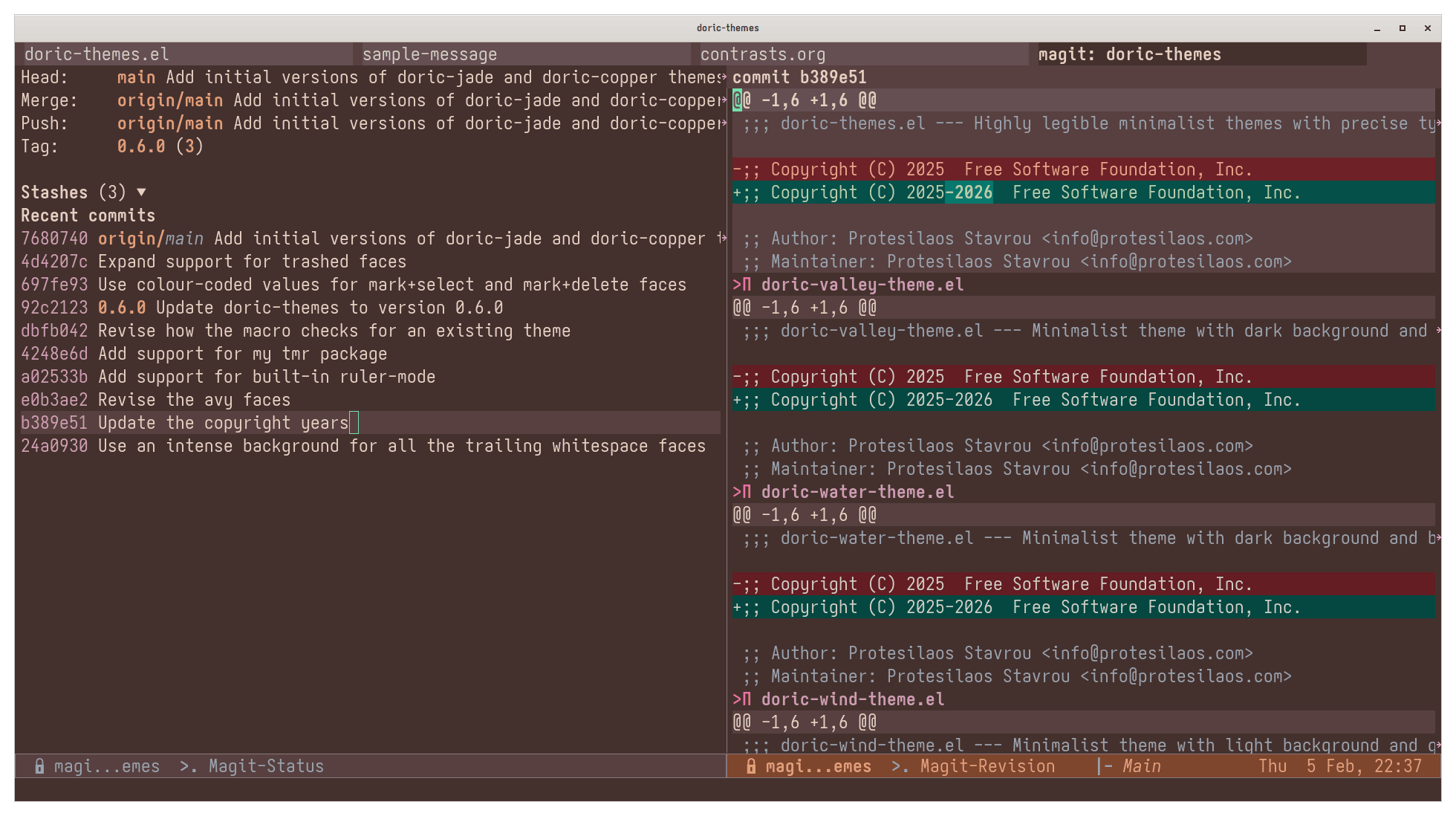

Code Navigation and Imenu

neocaml provides proper structural navigation commands (beginning-of-defun,

end-of-defun, forward-sexp) powered by TreeSitter, plus imenu integration

definitions in a buffer has never been easier.

The older modes provide very similar functionality as well, of course,

but the use of TreeSitter in neocaml makes such commands more reliable and

robust.

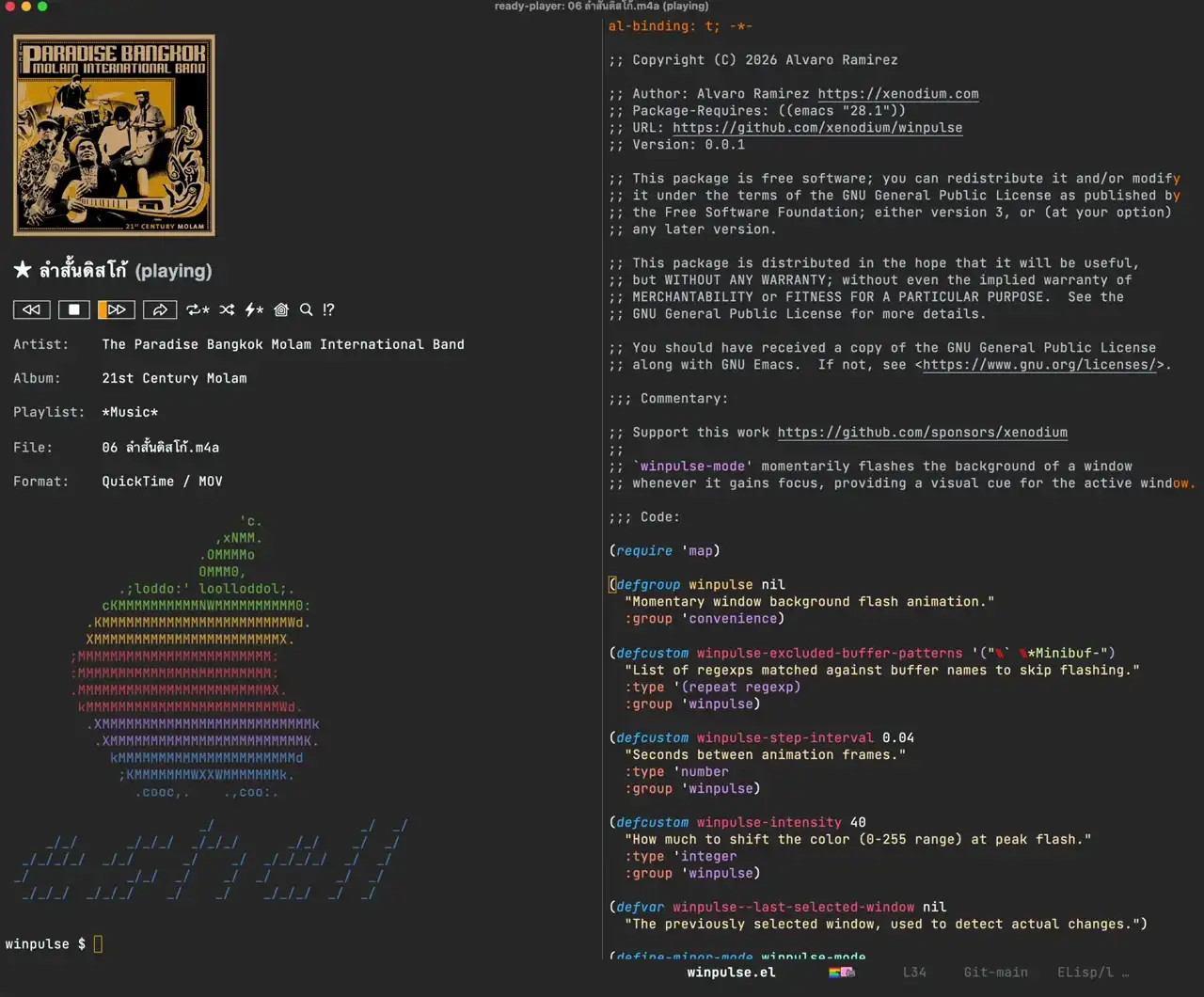

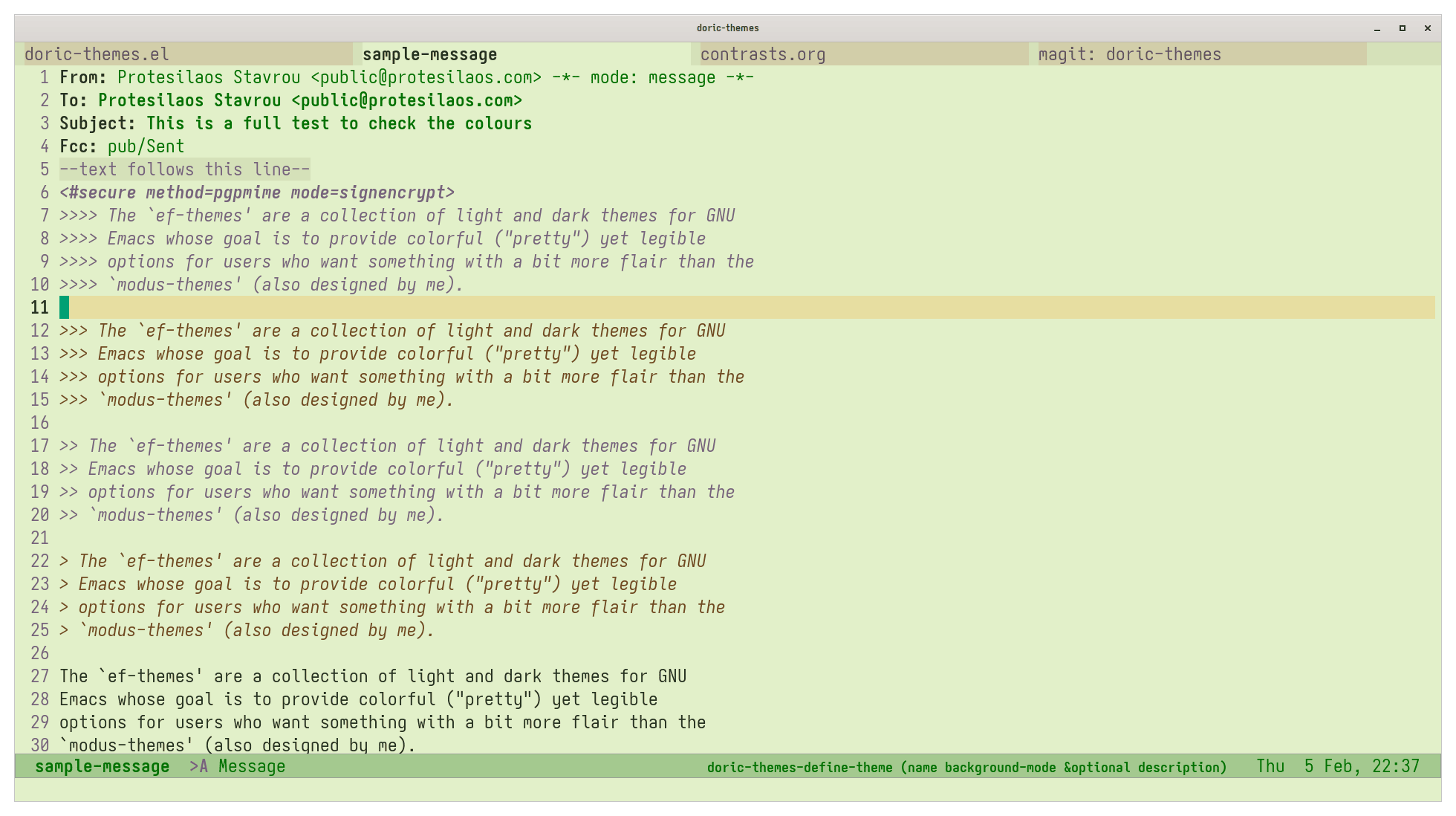

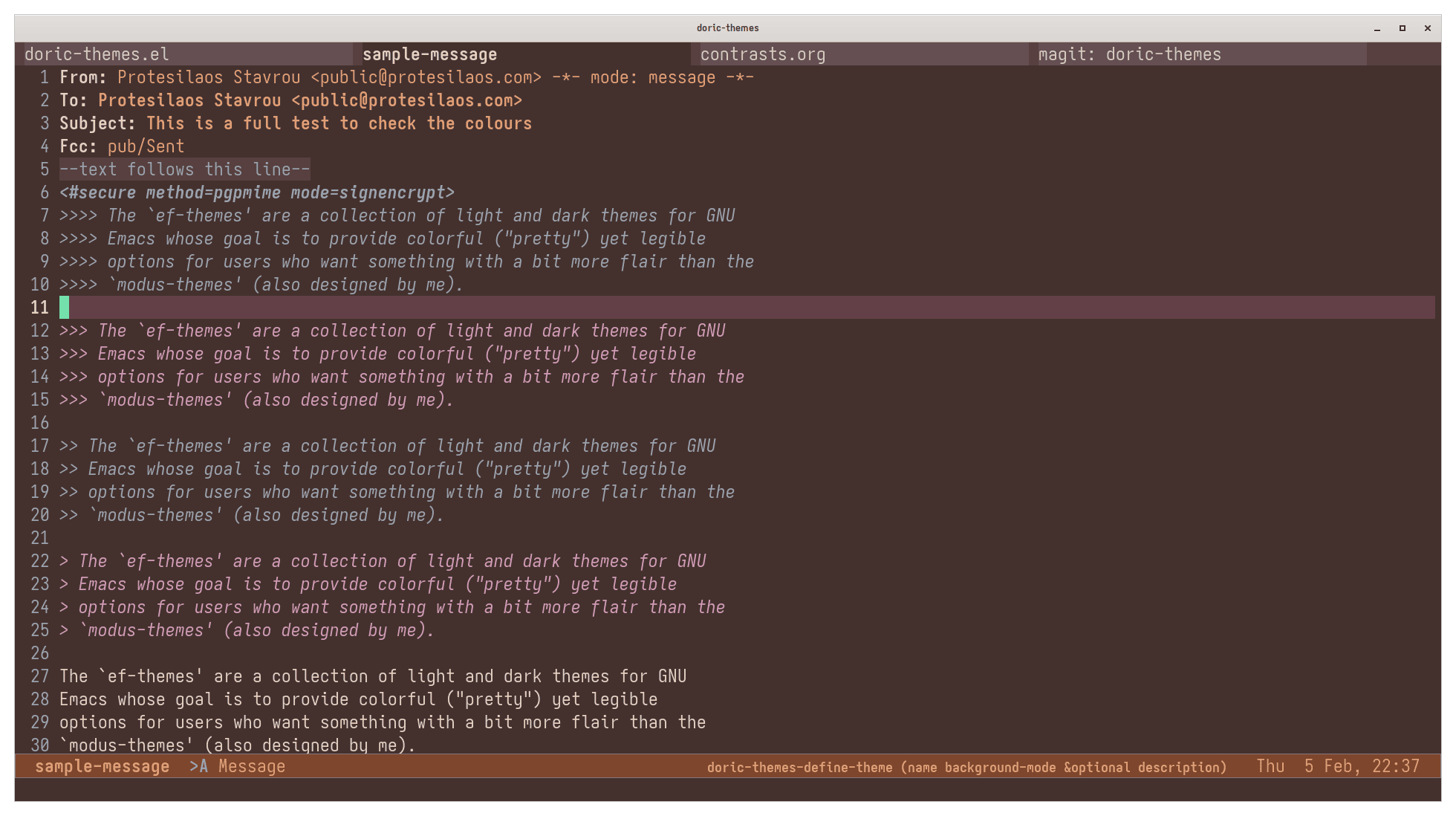

REPL Integration

No OCaml mode would be complete without REPL (toplevel) integration. neocaml-repl-minor-mode

provides all the essentials:

C-c C-z - Start or switch to the OCaml REPLC-c C-c - Send the current definitionC-c C-r - Send the selected regionC-c C-b - Send the entire bufferC-c C-p - Send a phrase (code until ;;)

The default REPL is ocaml, but you can easily switch to utop via

neocaml-repl-program-name.

I’m still on the fence on whether I want to invest time into making the REPL-integration

more powerful or keep it as simple as possible. Right now it’s definitely not a big

priority for me, but I want to match what the other older OCaml modes offered in that regard.

LSP Support

neocaml works great with Eglot and

ocamllsp, automatically setting the appropriate language IDs for both .ml and

.mli files. Pair neocaml with

ocaml-eglot and you get a pretty

solid OCaml development experience.

The creation of LSP really simplified the lives of a major mode authors like me, as now

many of the features that were historically major mode specific are provided by

LSP clients out-of-the-box.

That’s also another reason why you probably want to leaner major mode like neocaml-mode.

Other Goodies

But, wait, there’s more!

C-c C-a to quickly switch between .ml and .mli files- Prettify-symbols support for common OCaml operators

- Automatic installation of the required TreeSitter grammars via

M-x neocaml-install-grammars

- Compatibility with Merlin for those who prefer it over LSP

The Road Ahead

There’s still plenty of work to do:

- Support for additional OCaml file types (e.g.

.mld)

- Improvements to structured navigation using newer Emacs TreeSitter APIs

- Improvements to the test suite

- Addressing feedback from real-world OCaml users

- Actually writing some fun OCaml code with

neocaml

If you’re following me, you probably know that I’m passionate about both Emacs

and OCaml. I hope that neocaml will be my way to contribute to the awesome

OCaml community.

I’m not sure how quickly things will move, but I’m committed to making neocaml

the best OCaml editing experience on Emacs. Time will tell how far I’ll get!

Give it a Try

If you’re an OCaml programmer using Emacs, I’d love for you to take neocaml for

a spin. Install it from MELPA, kick the tires, and let me know what you think.

Bug reports, feature requests, and pull requests are all most welcome on

GitHub!

That’s all from me, folks! Keep hacking!